Sequencing What Items Invoker Will Use

In this blog post, I attempt to explore the use of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) in predicting what items Invoker players will purchase in standard DotA 2 matches. DotA 2 is a game managed by Valve (and lead developed by IceFrog) with team-based, player versus player, and role-playing elements. As with most role-playing games, there exists a diegetic component of a character build where a player must choose how the character he or she plays is developed. One of these elements of construction includes what items a player will purchase with in-game rewards in order to strengthen their character, and I attempt to predict this particular element with RNNs. The problem was limited to one of the characters of DotA 2 in higher level matches. This blog post will not focus on particularly difficult techniques; the network is actually a simple long short term memory (LSTM )cell, and the code runs on most computers within the past 5 years.

All of the code referenced in this post—including data gathering, pre-processing, and modeling—are included in this project. The frameworks used include NumPy, SciPy and TensorFlow (everything was written in Python). Special thanks goes out to the Stratz team for their assistance in obtaining data using their API.

So why even predict what items a player will buy as Invoker? This could be used as a tool to teach new players how to emulate higher level players. Professional players could explore lots of potential builds relatively quickly in contextual scenarios (although this model does not take into account the general state of a match). And if it works for items, it could reasonably work for skill progression or hero drafting.

Recurrent neural networks are particularly useful in environments where sequence and order matters such as natural language processing, audio and visual encodings, and stateful changes. DotA 2 is a game with a lot of conditions, states, and variables, and I only use a limited amount of information that a game contains, but the results seem initially promising. For this particular project, the network consists of a simple long short term memory cell.

The data was obtained by using the Stratz API. I was given a set of matches with a high level of skill by Ken of Stratz. For the players in these games, I then sought out their recent Invoker matches in patch 7.06e. Matches were limited to ranked All Pick or Captain’s mode games. For these games, I obtained their list of purchased items, and this was the data actually used in the model. There is additional data obtained that are usable as features, but I did not incorporate them this iteration. This includes past performance of allies and enemies on the hero of their choice. For example, if a teammate played Crystal in a particular game, I also gathered data for how that player did as Crystal Maiden in the previous 50 games in terms of the average kills, deaths, and other relevant pieces of information. Nonetheless, this extra information was not used in this model and was left as something of interest.

How does data transit through the network?

To cover the motivations and mechanics of RNNs in this blog post would be ambitious, but I hope it will suffice to say that an recurrent neural network uses its input and some vague history of the previous inputs to generate an output. A LSTM cell can be a component in a RNN because it tries to remember its previous output and its previous state. The previous output serves the function of being a short term memory for the cell, and the previous state serves as a long term memory for the cell. How does the network deal with the first prediction? The initial short term memory and long term memory are empty, and I always started with a few initial items to seed the item sequence generation process.

As mentioned before, RNNs are commonly used in natural language processing, so I will explain a bit of how LSTM cells work with a language example. Suppose that you wanted to finish a sentence such as “Jack and Jill tried to go swimming in stormy weather, but they had to ________.” You might use your idea within the sentence (your short term memory) to finish the sentence with “go back because the lake was dangerous.”

However, suppose that the entire sequence was actually “Jack and Jill live in the city. Jack and Jill tried to go swimming in stormy weather, but they had to go to __________.” The finishing sequence could be “go the indoor pool downtown.” The longer memory is certainly useful.

In the above examples, the current input would be the most frequent phrase “but they had to go to.” The short term memory would be the rest of the most recent sentence. And the long term memory could be some vague recollection of the previous sentences.

The cell uses the short term memory and the current input to learn what to forget from the long term memory with use of forgetting parameters. It also uses the short term memory and input along with remembering parameters to know what should enter the long term memory. Some of the forgetting and remembering parameters along with the old long term memory and incoming long term memory are used to generate a new long term memory (or a new state for the cell).

With this new state, the cell can generate output. A set of output parameters generates an final output using the input item, short term memory (the previous output), and the new long term memory (the new state). Finally, I map that final output the cell to probabilities of what the next purchased item will be. The item with the highest probability denotes what the next predicted item should be.

How does it learn to do this?

Given the matches that I collected, I partition this data into completely distinct training and test sets. The training set is used to teach the network how the parameters should be tweaked. The way it does that is that it tries to do a bunch of predictions based on the transitions of purchased item to the next purchased item for the item sequences (the different matches). If the prediction is wrong, then it tweaks the necessary parameters. The training process goes through many iterations of failed predictions and tweaks. If you want more details, look up (truncated) backpropagation through time. Some knowledge in linear algebra and basic calculus will help.

However, one must be careful to not use the training set to determine how good the model is. That is why we test on the test set. Sometimes, there is a validation set to evaluate the performance of different models. The model that performs best on the validation set is then used to evaluate on the test set to determine the final score for the model. However, I only made one model, and there wasn’t enough data to make all three different sets.

Some Results

One thing to keep in mind is that randomly guessing would have an average accuracy of about 0.4% over an entire item sequence. My model had an accuracy of about 55% on the test sequences with a standard deviation of 9%. It took about two hours to train on a three year old laptop.

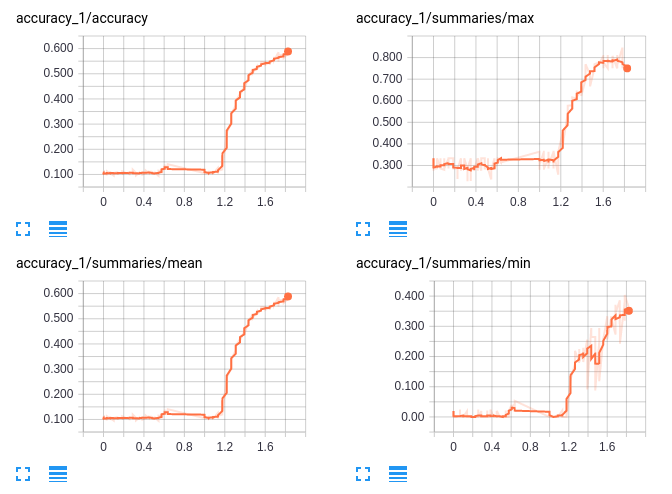

Here, I use TensorBoard to monitor how the accuracy of the model changes through iterations of training. You can use TensorBoard to see if there are any funky things going on with your model during training.

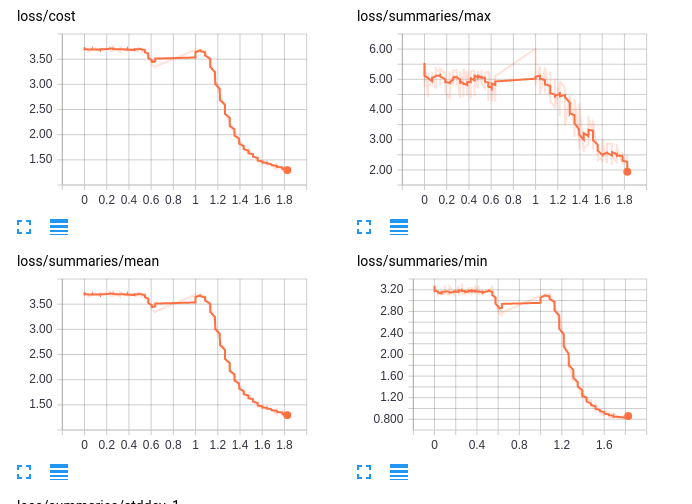

Similar graph as above, but I display the loss instead. The loss here was defined to be the cross-entropy between the target item and the predicted items. In a sense, this measures how disjoint the distributions were. As training goes on, the model performs better on the training set.

Here is part of an example sequence that the model generates when using a circlet, mantle, and null talisman recipe as the initial items:

- branches

- flask

- circlet

- mantle

- recipe_null_talisman

- null_talisman

- boots

- gloves

- tpscroll

- recipe_hand_of_midas

- hand_of_midas

- tpscroll

- tpscroll

- point_booster

- staff_of_wizardry

- ogre_axe

- blade_of_alacrity

- ultimate_scepter

- tpscroll

- recipe_travel_boots

- travel_boots

- blink

Here is a list of matches and their corresponding sequence accuracy (corresponding to top 3 and bottom 3 accuracies):

| match id | accuracy |

|---|---|

| 3293379090 | 0.762 |

| 3301460616 | 0.744 |

| 3308683837 | 0.738 |

| 3309468461 | 0.25 |

| 3306228851 | 0.25 |

| 3305013972 | 0.091 |

Possible Future Work

One thing I could have done is done is some processing on the sequences. For example, you cannot buy a Null Talisman, but you instead buy a circlet, mantle, and recipe in some order. Better grouping of items and mapping such as some combination of the Null talisman components into an indication of buying a Null Talisman could extract more meaningful signal. After all, it doesn’t matter what order you buy components of an item. However, I did not want to deal with situations with when people opt to not finish an item immediately. I could have also removed Null Talisman or any item that isn’t a purchaseable item and limited the number of targets.

I also forgot to take out from the sequences items that were context-dependent for buying, such as teleport scrolls or salves.

Lastly, I did not train on enough data. There were only about 1000 matches in this data set, which is arguably not enough given how dismal or “predictable” the predictions could be. The model can also be a lot more complex such as stacking cells.

And as mentioned before, you can include more game-dependent features such as what heroes are being used, the kill difference, or whether you need to be offensive or defensive (although this could be its own project).

Conclusion

RNNs seem to fit the right bill to predict Invoker items in most typical matches. This could easily be a tool to help new players learn item progression. If the model were to be built with consideration of the unused features such as the past performance of allies and enemies on the hero they have chosen, then the suggestions can become much more contextualized. The model and data themselves could be better refined. Nonetheless, the model does much better than random chance. Perhaps the same idea could be applied to hero drafting or skill progression.

If anybody wants to further build on this or just use the data, feel free to comment or just go straight to the Github! Thanks for reading.

References

- Some official TensorFlow documentation of RNNs

- colah’s excellent article on LSTMs

- Some practical features of the basic RNN cells and their wrapping libraries highlighted by Denny Britz

- Danijar’s article on variable length sequences in TensorFlow

- Another article on variable length sequences

- Stratz API